Tracy-Ann Oberman talks about playing Shylock as an East End matriarch in the upcoming tour of The Merchant of Venice

Tracy-Ann Oberman has always hated Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Since studying the play at school, she has been troubled by the extreme antisemitism of the characters in their language and behaviour towards the Jewish money-lender, Shylock. “I was deeply uncomfortable when everybody was laughing about, ‘My ducats, my daughter’, and going around doing impressions of Shylock rubbing his hands together,” she recalls, “and then laughing at the end as the old man had his beard shaved off and was dragged out having lost everything.”

Despite her antipathy, Oberman has decided to take on this problematic play and find a new way to approach its antisemitism – with herself as Shylock. She has teamed up with director Brigid Larmour on a concept that sees Shylock become a working-class matriarch in London’s East End in the 1930s when Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists was mirroring what was happening in Nazi Germany by attacking Jewish people. “I wanted to see what would happen if you took a strong female angry woman struggling as a survivor who has this one daughter, Jessica, who she wants to give a better life to as she is struggling against 1930s antisemitism.”

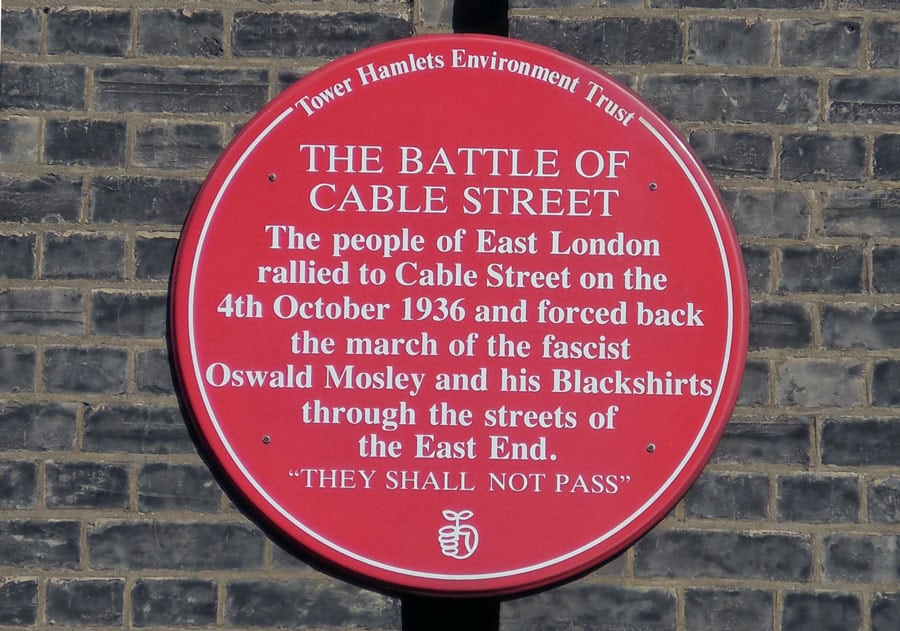

The production will open at Nuffield Southampton Theatres in September before going to Liverpool Playhouse, Watford Palace Theatre, Leeds Playhouse and finally Rose Theatre in Kingston upon Thames in south London in November. The tour will tie in with the anniversary of the Battle of Cable Street when, on 4 October 1936, the working-class communities of east London came together to drive away a protest march by Mosley’s fascist blackshirts. An estimated 20,000 people fought them off, using chair legs, rotten vegetables and other improvised weapons – and among them was Oberman’s own family. “The stories that I grew up with were of the strong matriarchs who stood on the front line with their daughters and their sons and turned over lorries and threw marbles from windows,” she says.

Her great-grandmother Annie had escaped the Russian pogroms in Belarus to settle in the Cable Street area with her husband Isaac, going on to run the family’s clothing business “with an iron fist”. There were two great-aunts, “Machine Gun” Molly, who also ran the business and Sarah Portugal “who wore a slash of red lipstick and smoked a pipe”. These “very strong matriarchal figures” have inspired Oberman throughout her life and now in her portrayal of a female Shylock.

Her family were also life-long socialists, Oberman points out. “They were a huge part of the formation of the trades union movement and the Labour Party.” This has fuelled her anger at the party’s failure to tackle antisemitism within its own ranks, leading to her being the target of vicious, hate-filled abuse on Twitter alongside others such as Rachel Riley. “My upset was that this was my party, it was my heritage, it was my history, it was my family.” She notes that the vitriol was also highly misogynistic, mainly targeted at women. However, her experiences have served to make her stronger in her activism and, with a broader rise in antisemitism in Brexit Britain, her new take on The Merchant of Venice is more timely than ever. “That play has really resonated with me as an activist over the last few years because I found myself on the front line, particularly on social media, of speaking out against a growing wave of antisemitism and anti-Jewish statements.”

An important element of the tour will be its education programme, with plans to highlight the popularity of fascism in Britain in the 1930s, especially among the aristocracy. This will include activities by Leeds Playhouse to highlight another key event, the Battle of Holbeck Moor on 27 September, only a week before Cable Street. Largely unreported at the time, it saw the British Union of Fascists set out on a march from the centre of Leeds towards a rally in Holbeck Moor south of the city, but they came up against around 30,000 people determined to stop them. Mosley himself was slightly injured after being hit in the head by a large stone. Oberman notes that her young daughter’s generation learn all about the civil rights movement in the US but nothing about it in the UK. “None of them know anything about the moment in Cable Street when Oswald Mosley brought his fascists to the streets here on the anti-Jewish ticket and all the working-class communities stood together and said you shall not pass. The bigger thing about this, which makes it so exciting, is that it will be a big education project that will go out and remind this country of our very own civil rights movement when working-class communities rose up to stand together against upper-class fascism.”

Larmour, who is artistic director of Watford Palace Theatre north of London, also says she hopes this production will help to remind people “how strong fascism nearly became in this country in the 1930s. It is dangerous to forget.” She is also excited about how Oberman’s concept “opened up” a play where the merchant, Antonio, and the heroine, Portia, set out to defeat a Jewish businessman with a young daughter. “When Tracy said she imagined this East End matriarch as Shylock, I thought, oh wonderful, this gives me a way into Antonio and Portia who, for me, are always very problematic characters. I thought we could talk about English fascism, we could talk about Oswald Mosley, we could talk about the aristocratic support for fascism that got rather forgotten in the story of the war. So I imagine Antonio as a kind of Mosley figure – charismatic – and Portia as maybe a rather better-educated Diana Mitford, which brings colour to the play. These characters are of course glamorous and fascinating – we want to see more of them.”

It is not the first time that directors have attempted to challenge the play’s antisemitism which reflected common attitudes to Jewish people in Elizabethan London. Casting Jewish actors as Shylock, modern productions have emphasised the tragedy of his condition, portraying him as a victim of the others’ mockery and manipulation. Some directors have also sought to highlight the flaws and reprehensible behaviour of the Christian characters, suggesting Shakespeare might have been questioning or exploring antisemitism. However, Oberman is determined not to make her Shylock a victim. “It doesn’t matter how many times I’ve seen a production of The Merchant of Venice or however it’s been framed, people either pity him or laugh at him, and I don’t know which is worse.” With the strength of her family and activism behind her, it is clear that her Shylock will not be a figure of pity but a portrait of survival.