Julian Eaves reviews Youth Without God, dramatised by Christopher Hampton and directed by Stephanie Mohr now playing at the Coronet Theatre.

Youth Without God

Coronet Theatre

23rd September 2019

3 Stars

Book Tickets

For anyone who thinks that history has a tendency to repeat itself, and who sees in the mood and drift of our times an uneasy parallel to what afflicted the world a few generations ago, then no better object lesson could be found than in Odon von Horvath’s stern novel, ‘Youth Without God’ (‘Jugend ohne Gott’). Published in Amsterdam in 1937, it depicts contemporary life in Germany under the National Socialists, seen from a small-town point of view, through the eyes of a local schoolmaster – a sardonically detached observer (rather like von Horvath himself?), who nonetheless is troubled by a need to seek out and find the truth. Horvath was essentially a dramatist, who only turned to writing prose because after the Nazis rose to power, he couldn’t get his plays put on. Over the years, various adaptations have been made, some of them going a long way to modernise and give immediacy and relevance to the story, some more traditional. Ten years ago in Vienna, Christopher Hampton, a specialist in taking European writers and putting them on the stage, presented his dramatisation, translated out of and then back into German by other hands. Hampton’s careful and respectful English-language version has now made it to bohemian Notting Hill Gate and the crumbling neo-baroque interior of the Coronet Theatre, just as the world around us seems to be sliding once upon into right-wing populist demagogy.

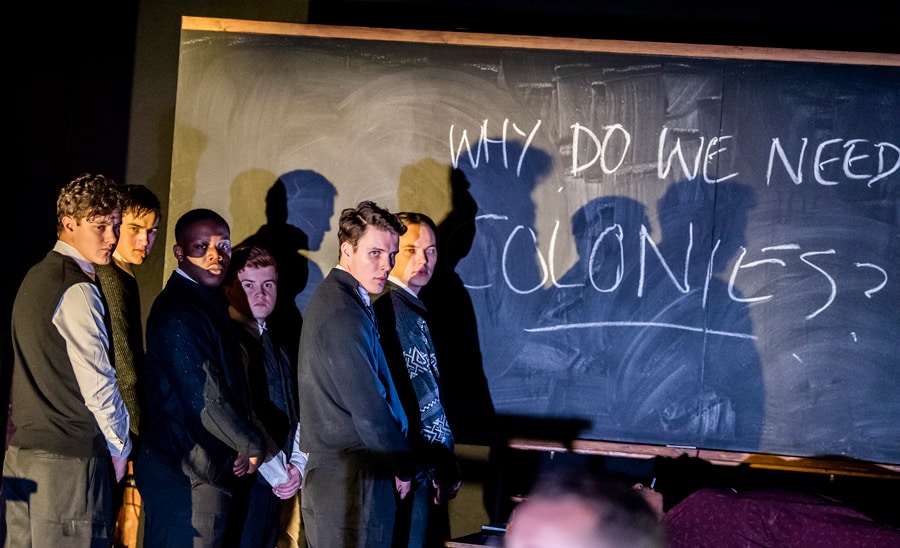

Directing this production is another new arrival from Central Europe and mainly German-speaking theatre, Stephanie Mohr, making her debut in the UK. Working with designer Justin Nardella, she gives us a period-feel interpretation, framed by three walls of blackboards, upon which the cast write and draw with white chalk as the narrative progresses. Six young adult actors, first seen with accordions slung across their shoulders, play the schoolboys – in long socks and short trousers – with one young female character, three men and a woman playing the other roles. For such a small theatre, it feels like a large cast. Yet, there is a sense that the production doesn’t quite know what to do with these resources.

The plot, such as it is, is a kind of thriller: in fact, it becomes a murder mystery. But who is leading it, and what is its aim? We begin with a complaining parent (one of Christopher Bowan’s many ably executed roles), before switching to the more serious investigations pursued by the schoolteacher (mild-mannered and curiously passionless Alex Waldmann) and the local prosecutor (one of David Beames’ multiple, well-drawn incarnations). At the same time, the young people are all doing their own snooping. Now, to catch this atmosphere of omnipresent spying and prying – and universal guilt? – is a tricky business, and it is only imperfectly realised here. The longer we stay with the play, more we feel we have a notion of where it should, or could, be going, and wonder at why it is not quite capable of getting there, or at least of making us believe that it is more definitely on the right track. There are some interesting elements, but they don’t quite feel as if they have all coalesced.

What is missing? Well, here’s one possible idea: the German theatre that I know stands full-square upon the richness of the language itself and an intensity of delivery that is quite shockingly direct compared with the more round-about, naturalistic approach favoured in the British theatre. While watching this play, I was constantly re-translating the dialogue back into German, thus: eg. ‘The moon disappeared behind a cloud’ sounds mildly pictorial in English, but ‘Der Mond verschwand hinter eine Wolke’ is packed full of the most extremely potent German Romantic symbolism, conjuring images of from Caspar David Friedrich (et al) and all the philosophical, ‘weltanschauliche’ power of the riposte to Enlightenment values that presented itself in the establishment of German nationalism. All of that simply cannot be conveyed by ‘The moon disappeared behind a cloud’. Other means must be drawn upon the make that drama speak. But what means, and how should they be articulated?

That, if you like, is the problem that the Coronet has set itself in staging this fascinating work. It’s a bold move for this experimental and risk-taking house. I have seen other productions handsomely succeed in this. At other times, the gambles don’t quite pay off. Here, you can find things to enjoy. There is the occasional urgent gravitas that career debutant Finnian Garbutt finds as one of the boys, Franz Bauer. Anna Munden manages to create a lasting impression with her under-written part of Eva. Nicholas Nunn displays some menace as Dieter Trauner, while Malcolm Cumming most tellingly appears as a ghost. However, the lost melancholy of Raymond Anum as the vacillating Robert Ziegler doesn’t help him to reconcile the odd contradictions in his part. Owen Alun (Heinrich Reiss) and Brandon Ashford (Arno Feuerbach – what a philosophical name!) complete the squad of boys. Clara Onyemere perhaps has the toughest job of all in her very sketchily constructed three roles.

With muted lighting by Joshua Carr and very variable volume levels in the sounds from Mike Winship, this is a production that it is difficult to feel at home in. That’s a shame. The original novel was praised highly by Thomas Mann, and it’s easy to see why. Horvath and Mann share many of the same aesthetic and philosophical traits. Horvath’s language is more robust, sprightlier than Mann’s, I think, doubtless thanks to his growth as an artist in the realm of the spoken rather than printed word, but they have in common a love of the culture they both saw threatened by the barbarism of the Third Reich. Both are obsessive chroniclers of the struggle between the virtues and the vices of the German-speaking world. In these days, it is well worth reminding ourselves of this fact, even if only through an imperfectly realised of this difficult but intriguing work.