It was announced this week that, due to unprecedented demand, Headlong’s 1984 is extending its run at the Playhouse Theatre until August 23rd, prior to its second UK tour. The play itself reminds us of the dangers of following suit. The popularity of this anti-populist play therefore is a particularly pertinent indicator of some significant shifts in theatre.

Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillian’s 1984 is more harrowing, chilling and stimulating than it is enjoyable. A bit like spending 1hr 41 minutes in a refrigerator – cold and bright – 1984 is brilliant if you like your theatre heart free and served up over ice.

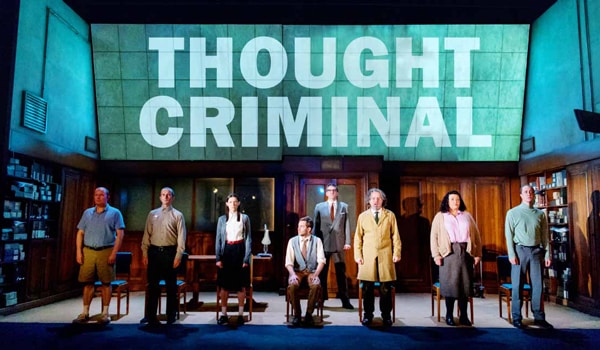

This is innovation as well as imitation; truthful to the novel and yet bold with interpretation. The writer-directors embrace the novel’s appendix, using it a framing device. The play gives voice to the book’s accompanying comment, opening in the seemingly familiar territory of a discussion group where one is entitled to the luxury of reading, passing comment and pouring over literature, even if mobile phones do cause a continuous stream of interruption and irritation. This creates the perception of a recognisable present day. You’re comfortable with the context and think you know where you are, but this rapidly dissolves leaving disorientation to take hold. For the remainder of the piece an emulsification of our past, our present and our future renders 1984 timeless and placeless. 1,9,8 and 4 become meaningless digits, as here 2+2 equals 5 (or whatever Big Brother says it does). Representative of every place and every time, Headlong’s incarnation of Orwell’s dystopia (“A vision of the future, no matter when it is being read”) is too accurate a reflection of all humanity to observe in comfort.

Sam Crane plays a sensitive, mild-mannered Winston Smith, compelled to write down his plight in a futile attempt to cling to what remains of the truth. His job to erase records, images and people from Big Brother’s database at the Ministry of Truth is reminiscent of the Nazi book burning in Berlin in 1933. Deleting anything that threatens or questions authority ultimately leaves Winston fearless of the fight. In a world without chocolate, orgasms or free thought, where ignorance is strength, where the principle of Newspeak sees to it that ‘unnecessary’ words are erased, what does he have to lose? These heretical thoughts, along with belief in the existence of the Brotherhood, put Winston at serious risk.

It is (perhaps intentionally) difficult to connect to, or feel for, any of the play’s characters. Winston is Everyman and those who exist alongside him effectively represent human kind. He finds reassurance of sanity and some mutual ground in Julia, played by Haran Yannas, but her rapid leap to love and his rash reciprocation, despite her being only “free from the waist down,” are difficult to be convinced of. This undermines the shame of betrayal that becomes central later and prevents the audience from feeling much beyond despair at the bleak state of the whole human condition. Cheers guys.

The set, lighting and sound designs by Chloe Lamford, Natasha Chivers and Tom Gibbons transform a stoic, drab study into the clinical, stark Ministry of Love in a matter of seconds. The exhilarating assault on the senses – visceral, nauseating – begins the process of implicating the audience, consuming us, drawing us in. The reverberations of this staged reality are inescapable so that we can all experience life under Big Brother’s regime. We are kept at a distance from any of the love, hope or happiness, all played through a live video link up. The audience are allowed to see a curated experience of these scenes via a telescreen. This detachment adds further to the evocation of the frozen, controlled, rational 1984 and rings alarmingly true to the culture of screens and surveillance (for our ‘safety’) that we have long become accustomed to. We have a close-up view and a zoom function, but are somehow further away from reality.

Headlong are at risk of eating themselves – on the verge of being a tad too aware of their own intelligence – but it’s impossible not to appreciate the cleverness here. Satisfaction comes in jolts when you finally think you know where you are, even if just for a scene or two. But Icke and Macmillian are always in control, manipulating from beginning to end – this, their strategic game of chess and us, an audience of pawns. There’s nothing worse than the way you are made to feel as the action turns outward and the full auditorium become complicit in the work of Big Brother – each as guilty as each other. Like in Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, those who control and indoctrinate are as dangerous as those committing crimes. Are we being prompted to get up and act? Are we supposed to have been able to save Winston from what seemed like such inevitable fate?

All in all, writing about 1984 is futile. I am fortunate to have the liberty of language and freedom from the thought police, but in order to honour the play’s message, don’t take my word for it. Experience it for yourself and make up your own mind. I, after all, can’t tell you what to think. All I do know is that you’re likely to need a ‘victory gin’ after.

When theatre such as this hits the main stream, the form’s potential is fulfilled; it has the power to change minds and challenge politics. Headlong, knowing that “an idea is the only thing that ever changed the world,” have tapped into this and are bravely leading the way. But as it stands, too much theatre is reminiscent of the play’s premise and Big Brother’s regime. It is lavishly capitalist, with the wealthy, the branded and the familiar holding the reigns. For a supposedly artistic industry (art not science) there are a lot of rules, restrictions and ties that prevent genuine freedom of thought and expression.

Consider theatre’s latest trend: the phenomenon of the West End transfer.

Headlong’s adaptation of Orwell’s seminal novel is excellent. There’s no denying the benefit of this transfer and more people having the opportunity to see this show. However, something about the press coverage heralding this West End transfer as the be all and end all for 1984 contradicts the play’s message. Are London venues and audiences of greater importance to Headlong than their (often larger) touring ones? Of particular irritation was the comment in the Evening Standard that this piece “deserved to transfer to the West End.” What does that even mean? It’s not that I disagree, but how true is it that anything can be deserving of a place in a forum that inevitably prioritises commercial gain? Rarely (never) are the decisions to produce a piece for the West End based on artistic merit and quality alone. By claiming that some productions “deserve to transfer” suggests that you also have the power to decide what doesn’t.

Are we still naïve enough to think that the West End is where this country’s best work resides? Really? The West End is not, and never has been the meritocracy that it is commonly believed to be. To be in West End, a theatre needs to be a member of SOLT where the main requirements are a membership fee and a promise to produce commercial work. This isn’t necessarily the best work. If we continue to congratulate work for being in a West End theatre we will ultimately discourage writers and directors from developing anything that isn’t commercial and belittle the experimental, the intimate, the exclusive, the challenging.

Theatre is expensive so buying tickets involves taking a risk. It is natural, therefore, that we chose to see what is familiar. You could argue that 1984, despite being unconventional in form, was bound for commercial success because of its branded title. Still, more and more theatre is creeping in from the bottom up, coming out of the fringe, out of intense development, building momentum, whilst shows with enormous commercial value and financial backing are stacking it at the first hurdle. What this play’s continued popularity tells us is that audiences are committing a thoughtcrime or two. Increasingly discerning and politically driven audiences are starting to demand more than entertainment. Just look at the success of The Book of Mormon and the impending transfer of The Scottsboro Boys, for example.

There’s no equation, nothing to say what will be a hit and what will flop. Producing is taking calculated risks and, like with any gamble, there are many, many variables. Do you think that the National knew that War Horse was going to explode? Nick Hytner, on press night, predicted it would make a million pound loss. Ultimately, art will always be art. All we can do is continue to celebrate innovation and support ideas, developments, tradition and humanity, be open to change and embrace as much and as great a range as possible. And if theatre were to one day be a meritocratic industry then, my god, it would be a powerful force worth reckoning with – a force worthy of Winston and his futile rebellion against Big Brother – but alas, we’re not there yet.

PS: Is a transfer always a good thing? If, like me, you’d rather be poor and brilliant than rich and a bit shit then you might consider your original venue more appropriate for your specific piece, might you not? To be continued…