Julian Eaves reviews Faith, Hope and Charity by Alexander Zeldin now playing in the Dorman Theatre at the National Theatre.

Faith, Hope And Charity

Dorfman Theatre, National Theatre,

17th September 2019

Book Tickets

Lord Cottesloe once lent his name to one of the three auditoria at the National Theatre’s South Bank home; now he is only present in a single function room into which, at the opening night of this new play, written and directed by Alexander Zeldin, the press were herded at the interval. Nearly completely unfurnished, there is a large bookcase at one end, onto which are heaped very many playscripts and also books written by playwrights. Amongst those, the one that caught my eye was Arnold Wesker’s thoughtful and provoking ‘As Much As I Dare’. I pulled it off the shelf and decided to play ‘draw the sortes’ with it: randomly allowing it to fall open at a point and letting my eyes fall unguided onto whichever words lay closest to the focussing of my gaze, and from those words taking spiritual guidance, the better to navigate my present journey. Fascinatingly, this is what I read, words not of Wesker, but quoted by him: ‘… keep away from prose… stick to the poetry…’ It was guidance given to him when he was a young writer. Although I am far from one to subject the Almighty to ‘higher criticism’, I nonetheless felt I needed an insurance policy to back up this position: after all, what I had read were not the words of Wesker himself, but ‘found’ words. I required something from his voice. Thus, I picked up a second volume, a copy of his ‘Social Plays’, and out of that fell this magical line: ‘The truth is the truth – devastating’.

With these thoughts ringing in my mind, I returned to the auditorium to complete watching the first night of this piece with such a religious title (drawn from 1 Corinthians, 13:13, in the King James Authorised Version of the Holy Bible: ‘And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity’). The title is pretty much the only mystical thing about the play. Everything else is stark, hum-drum, hyper-realistic banality, where Marc Williams’ harshly bland full-on auditorium lighting draws us into the same charmless world as Natasha Jenkins’ super-naturalistic set (she dresses the cast with the same pitiless ordinariness). However, in amongst the breeze-blocks and plywood panels, Jenkins does throw in a trinity of Neo-Neoclassical Non-conformist chapel windows, hinting (which is more than the script ever does) at some lost sense of religiosity – the central one is slightly taller than the other two.

As for the rest of the play, well, there’s not really much to it, and it is quite devoid of poetic inspiration. A kind of re-visiting of Gorki’s ‘The Lower Depths’ – set in a day centre for the homeless, dispossessed and distressed – it is a poor relation indeed, lacking in almost all respects. I don’t know how many in the audience had spent much time living in the conditions depicted on stage. I couldn’t tell you how many had themselves experienced personal homelessness, poverty, hunger, cold and isolation, but for many years these were dominant features in my life, and in the lives of those with whom I came into contact. That reality, however, is not something I recognised in Zeldin’s confection. He has, apparently, heard the voices of the people he represents, he has seen their society: that much is laboriously and I am sure sincerely recreated here. But without the guts and without the spirit. It is a kind of ‘halal’ theatre: a picture of life taken and slowly bled to death before it is served up to the public. Superficially, it seems plausible; but pay attention closely and it all soon betrays itself as a fraud.

This is a world populated exclusively by losers. Having known only energy and vitality in the poor, desperate and marginalised, it came as quite a shock to have to sit through two and a half hours of weakness, complaint and regret, excuses, denial and blame, framed in such a self-consciously artless and would-be convincing way, so earnest is it in its efforts to trick you into believing it is real. The people in this room sit and talk and talk and talk with a singular lack of vividness and dynamism in a manner that is so foreign to what I experienced, right here in London, for so many years. The plain chat is almost interminable, recounting always at second-hand events that might have made an engrossing drama – had the director-writer allowed them to.

Ostensibly, this is the realm of Cecilia Noble’s ‘Hazel’, the matron – without anything but the most belatedly sketched in ‘back-story’ – whose saintly ministrations keep the glorified soup kitchen going. Hers, like most in the cast, is a patient and tolerant performance that is at pains not to draw too much attention to the woeful inadequacies of the text, construction, style, manner, etc. of the production. However, from the first scene it is clear that her dramatic purpose is something else entirely: it is to be one of several women who orbit around a much more important figure, a man, Nick Holder’s blandly officious interloper, ‘Mason’. In theory, he is there to run a ‘choir’, and in a sense there is a ‘plot’ which builds to the shattering climax of them actually running through a couple of pop tunes (think David Greig’s sooooo much better ‘The Events’ and dilute with 10 parts of cold ditch-water). But I think his dramaturgico-aesthetic raison d’etre is something else altogether. From the first, Hazel cannot take her eyes of him; and soon enough Susan Lynch’s text-book fractured failed-mum, ‘Beth’, is repeatedly throwing her arms around him, showing him her naked breasts, and smothering him with passionate kisses. What a guy.

Meanwhile, Dayo Koleosho’s ‘Karl’, Corey Peterson’s ‘Anthony’ and Nathan Armakwei-Laryea’s nameless ‘Ensemble’ role all get ignored. So does Bobby Stallwood’s (admittedly only 16-year old) ‘Marc’. In terms of sexual politics, it’s ‘interesting’ to see this happen. Oh, did somebody mention politics? You know, I think, somewhere, behind all the plastic chairs and paper napkins, there is meant to be some ‘implicit’ discussion of, um, I believe the technical expression is ‘searingly topical’ issues of the day. But, and it is a big but, Zeldin ensures that no-one is ever allowed to come on stage to give them physical form, as a journalist, or councillor – I think the programme calls them ‘counsellors’ – or any incarnation of authority that might conceivably trounce the only permitted alpha male, ‘Mason’ (with his name so redolent of ‘builder’, ‘member of secretive self-help organisation’, etc.). Hmmmm….

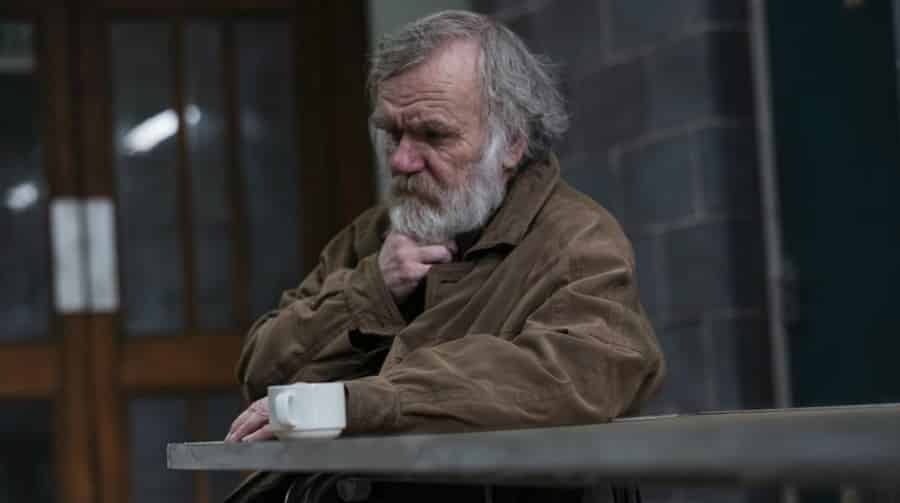

The result is a play full of words but utterly lacking in drama. That did not bother the first night audience: most of them dutifully laughed and chortled through the talk-show on stage, and then jumped to their feet at the end of the ‘performance’ to cheer it to the rafters. And I honestly couldn’t comprehend why. I don’t know. Maybe I’ve got it all wrong. Maybe they all know what this kind of world is really like, and it’s me that doesn’t. I’ll happily stand correction. Meanwhile, we have underwritten parts for Hind Swareldahab’s ‘Tharwa’ and her stage-child, ‘Tala’ (Kamia Hunte, Ayomide Mustafa or Ashanti Prince-Asafo), plus the wasted supernumeraries of Sarah Day, Shelley McDonald and Carrie Rock – all more distantly orbiting satellites. Marcin Rudy contributes a teensy bit of movement. And then there is the constant whingeing and apologising of Alan Williams’ ‘Bernard’. Of all the things I remember about people from this milieu, not one of them ever felt they had to say ‘sorry’ for who they were or what they did. And so they never did. There are a few under-prepared, under-powered outbursts here, but nothing ever builds up the necessary impetus to go anywhere.

This makes it all sound very stale and pre-digested, with every potential thrust of theatrical drive thwarted before it has a chance to develop. From my admittedly limited and quite possibly hopelessly warped perspective, this is so disappointing. These people from the lower depths of society are those who, in my experience, seldom lose any time in coming straight to the point, yet here they never even seem to begin to grasp it. I close with one final example: Once, when getting a haircut, a local lad burst into the barber’s, keen to sell – quickly, for cash and no questions asked – an expensive camera that had just come into his possession. He approached me with his offer. I asked some evaluative questions about the apparatus. He breezily but politely dismissed my enquiries with, ‘I’m a thief, not a photographer’. I would suggest that that individual understood more about concise, wittily-crafted dialogue that makes a sudden and indelible dramatic impact than the careful, plodding Mr Zeldin will ever know. The truth really is the truth – and it is devastating. And it is precisely what you do not get here. There are well-meaning contributions from the cast and creatives, but nothing can solve the short-comings of a verbose, static, lifeless script.