The Gin Game

Golden Theatre, Broadway

15 October 2015

3 Stars

Buy Tickets

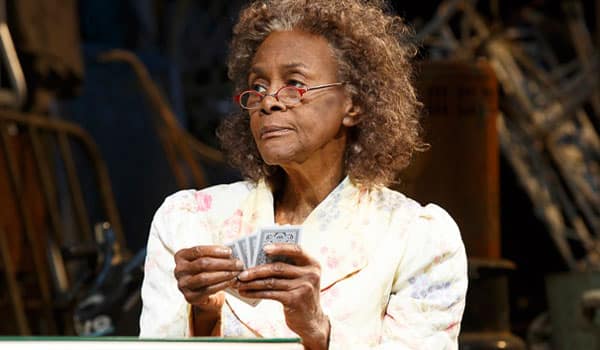

She is frail, wiry, intelligent. She might be ill, but there is a vivid sense of life about her every fibre. She may be 90 years old but time has not dismissed her. She has a quick smile, a sharp tongue, piercing eyes – you don’t get the feeling that much gets past her. But she is undeniably old. And she seems very alone.

He is a bruising hulk of a man, or, rather, the remains of a man. He too seems very old, though not quite as old as her. He is much taller, much broader, much thicker, a great bear of a man. His eyes are bright, but not as bright as hers; he moves more slowly, but there is a clear sense that he could move quickly if he wanted. His temper is explosive, a matter demonstrated very early on.

He encourages her, coerces her to play Gin Rummy with him. He wants to win; she always does, whether she knows the rules, the game or the safest course or not. When he upturns the card table in uncontrollable rage about her prowess with cards, you cannot but fear for her safety. He could easily snap her neck in a fearsome rage.

My fellow audience members, though, thought it was funny.

This is the revival of The Gin Game, D.L.Coburn’s Pulitzer Prize winning play, directed by Leonard Foglia and now playing at Broadway’s Golden Theatre. When it first was produced on Broadway, in 1977, it starred the husband and wife duo, Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn. It did not win a Tony Award for Best Play, but Tandy got the gong for Best Actress. How it won a Pulitzer Prize is anyone’s guess, for it is a slight and uncomplicated piece of writing, Coburn’s first play for the theatre.

The secret, one suspects, lies in the chemistry of the two players. With Tandy and Cronyn, it came in-built: this is a play about strangers coming to find their similarities, their fusion points, testing each other’s limits. For Tandy and Cronyn, it must have been like breathing, as the film of their performance suggests. Other productions have relied upon similar chemistry : Mary Tyler Moore and Dick Van Dyke; Julie Harris and Charles Durning. The chemistry between the two old combatants is really the key.

And there is no denying that Cicely Tyson and James Earl Jones have chemistry, the kind of chemistry that a bruising battering husband and his long suffering wife have. It’s fearful, fearsome, emotionally charged, and totally believable: thousands of woman around the world, Western and Eastern, know that sort of relationship well.

It’s just not funny. At least, not funny in my view. Audience members around me guffawed endlessly, even when tears were forming tragically in Tyson’s eyes, even when Jones was himself appalled at what he had done but kept on doing it. What, however, is funny about a man violently assaulting a woman, with words, intentions, thoughts and actions, especially when he knows it makes her scared?

The performances seemed to me to be finely judged, perhaps going to a place where earlier productions had not gone. There is a rawness, a bruising edge to Jones’ exasperation which is steeped in male-on-female domestic violence. There is nothing wrong with that, it is a reading which works perfectly. It just does not result in a pleasant night of cute laughs at the theatre.

This is the great problem here. These well loved actors are loved because of who they are, what they have done before, rather than what they do here. In typical, obsequious Broadway fashion, they are applauded on entry, before they have done anything to warrant applause. This sense of “they are stars” permeates the action, lulls or permits the audience to believe that the play will be a good, fun time. Or perhaps the audience just expect that and insist upon it as their reaction.

To me, however, that is unfathomable.

Both actors here are doing something quite different from a drawing room comedy. They are trying to make a point and, bravely, one that extends beyond the Caucasian community. Ill-treatment of women is everywhere and it must be stopped – that is what this version of The Gin Game screams. It’s just that no one seems to be listening.

Tyson is particularly effective. She is marvellously alive and agile as Fonsia, the retirement home dweller who still wants to live and who, most of all, wants companionship. She practically begs for Jones to adopt her as his mate, and her “rebellions” against his bad behaviour have all the hallmarks of a battered, loyal wife. The scene where they dance together is achingly tragic – it shows what they could have, if only both, not just Jones, but both, would let it happen.

Because, Tyson’s Fonsia insists on being the smartest. Fair enough, as she clearly is. But her persistence in this has consequences for her; Jones’s anger and upset and, possibly at the end, outright rejection. Is this the right result for her? Would letting him win now and then – called compromise in couples therapy, I believe – permit a happier co-existence?

Is it better for Fonsia to assert her intellectual cunning over Jones’ Weller always? As they delve into each other’s lives and weaknesses while playing Gin Rummy, is it necessary for her to rub his nose in her cleverness? Should it matter so much to him that she does? Should she forgive his violent, tempestuous physical aggression or do what she can to ensure that aggression never coalesces?

These are questions which lie at the heart of great drama. The Gin Game may not be in the league of great modern dramatists, but this production gives it a chance to aim for that pitch. Tyson understands that; it is not clear that Jones does, or could.

Without doubt, Jones has one of the great theatrical voices. His deep, ocean-bottomed basso profundo sounds are really extraordinary, and when he takes the time to allow his voice to soften and glisten, he is truly remarkable to hear on any stage. There is a sonorous rigour which is seductive. But, equally, he cannot shake off the lustre and image of Darth Vader (and why would he!) so unless he works very hard at it, the sense of danger is an ever constant.

So, in this production, Jones becomes the retirement home Stanley Kowalski, capable of real violence but not necessarily intended violence. He feeds off Tyson’s rabbit-like Fonsia with real skill – both make the hunter and the hunted quite clear. The trouble is that the text really sees Fonsia as the hunter…

Actors being actors, they take their cue from the audiences. Laughs come. And so the performances are tweaked to suit and achieve more laughs. It’s understandable.

But, it is also simply wrong. With this cast, this is not a comedy. It’s a stark, marvellous drama about the battles of the sexes and how those battles don’t diminish with the effluxion of time. Anthony and Cleopatra can be found in retirement homes, playing Gin Rummy and testing and teasing each other. Age does not diminish in-built traits reinforced by society.

Foglia must burden the responsibility there. If this was meant to be a chance to re-imagine this play for a new audience, for new times, with utterly different central combatants, it fails. It could have been a red-hot, searing exploration of sexual and societal dysfunction – and with this cast, it might have been. Tyson could definitely do it; Jones, probably, with the right directorial vision.

Instead, the play aims for the loathsome middle ground, where violence against women is funny and the audiences find it so. Taking the road less travelled by, as Robert Frost knew all too well, would have made all the difference.