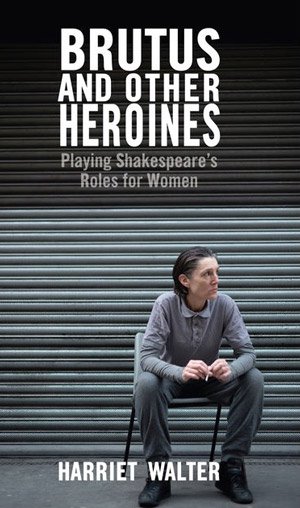

Brutus and Other Heroines

Brutus and Other Heroines

by Harriet Walter

Nick Hern Books

Four stars

Purchase a copy through Amazon

Harriet Walter has played nearly all the great female roles in Shakespeare from Portia in The Merchant of Venice to Cleopatra and Lady Macbeth. Entering late middle age, she felt that no new parts were left open to her – until director Phyllida Lloyd opened up her mind to the possibility of taking on some of the great Shakespearean male roles. In her illuminating new book, Brutus and Other Heroines, she takes us through the processes and thinking that led to Lloyd’s ground-breaking all-female versions of Julius Caesar and Henry IV.

Her book reveals the questions they tackled before going ahead with the first of the productions which saw Walter play Brutus at the Donmar Warehouse in 2012. For her, it was a question of “permission” – whether she and audiences would accept an all-female Julius Caesar as something worth doing and not just a vanity exercise. “What could I as a performer bring to any male role that a male could not do better?” Drawing parallels with the sexist attacks on Hillary Clinton in last year’s presidential election, Walter analyses why she as a woman didn’t feel people would consider her suitable to play a classic male role. “I had a typically female attitude,” she confesses. “I didn’t feel entitled.” Even after this soul-searching, they felt they still needed a reason why all the parts should be played by women, coming up with the concept of it being performed in a female prison. This turned out to have several benefits in terms of staging and also provided “a perfect metaphor for the way women’s voices are largely excluded from the centre of our cultural history”.

The second production, Henry IV, saw Walter play the title role in a two-hour version of both Parts 1 and 2, premiering at the Donmar in 2014. As in Julius Caesar, some scenes take on a new dimension when played by women, Walter points out. When Hotspur, Glendower and Mortimer argue over carving up the country after battle, the male posturing became more of a “boy’s playground squabble”, she recalls. “With women in the roles, we could highlight the preposterousness of certain aspects of male behaviour.”

However, much of the book’s exploration of the roles of Henry IV and Brutus is about much more than just gender, providing fascinating insights that come out of researching, rehearsing and performing them. This is at the heart of the book as a whole which provides in-depth analysis of the Shakespearean roles that Walter has played, although still putting them in the context of the role of women within the plays and the period they were written. Walter looks at how an actor can tackle female characters existing in a patriarchal society that sees women in male-centred definitions of virtue and chastity. She also touches on the fact that Shakespeare was writing his female roles for boy actors and how that may have allowed him to write better roles for women, including bawdy humour that only a man would have been permitted to speak.

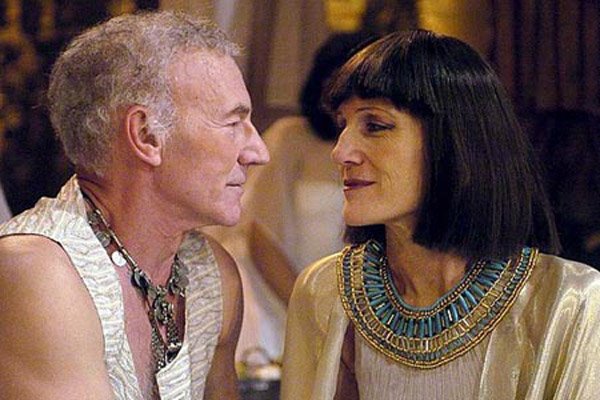

Walter throws new light on the young heroines who pose as men and the impact this has on the other characters as well as the audience, from Portia in The Merchant of Venice at Manchester’s Royal Exchange in 1987 to Viola in Twelfth Night, Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing and Imogen in the rarely performed Cymbeline. In discussing Helena in the problematic All’s Well That Ends Well, she sees her positively as an imperfect heroine who proves herself through deeds rather than the conventional female quality of passive virtue. She extends even more beyond gender in the chapters on the great tragic roles of Ophelia, Lady Macbeth and Cleopatra, giving us a sense of how performances evolve through rehearsal and even after opening. Throughout the book, she provides general observations about text and performance that will be of interest to scholars as well as actors of either gender playing those characters.

Walter went on to play another great role, Prospero, in Lloyd’s third all-female production in 2016 although this was too late to be included in this volume. She expanded on some of the themes of the book during a Platform event at the National Theatre on March 31, highlighting how many Shakespearean roles are about status and not just dependent on their gender. “Prospero was probably the most liberating of parts I have played,” she told the audience. “I did feel incredibly gender-fluid in that role. With Prospero, I just thought I’m not a father or mother but a parent. I am an older person facing the end of my life, letting my child go, trying to forgive people, making peace with the world.”

Walter believes Lloyd’s three all-female productions and other actors’ gender-swapping performances show there is more potential for women to play male parts. However, in a moving epilogue to the book, she sums up her frustrations that Shakespeare did not create more big roles for older women after Lady Macbeth and Cleopatra. “I am now what you would consider a very old woman, and I have felt somewhat starved of your material for the last 10 to 15 years,” she says in a heartfelt letter to Will Shakespeare. She applies the Bechdel test to his plays, finding only one scene (in Henry V) where two women talk to one another about something besides a man. “Our stories matter not because of our relation to men but because we are members of the human race. Are you not interested in our lives? I so want to be included in your wise humanistic embrace.” With directors and actors breaking down the barriers over gender more than ever in theatre, that embrace will no doubt become wider.